- Home

- Simon Jacobs

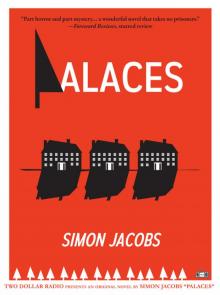

Palaces

Palaces Read online

SIMON JACOBS

Palaces

a novel

WHO WE ARE TWO DOLLAR RADIO is a family-run outfit dedicated to reaffirming the cultural and artistic spirit of the publishing industry. We aim to do this by presenting bold works of literary merit, each book, individually and collectively, providing a sonic progression that we believe to be too loud to ignore.

TWODOLLARRADIO.com

@TwoDollarRadio

Proudly based in

Columbus

OHIO

@TwoDollarRadio

/TwoDollarRadio

Love the

PLANET?

So do we.

Printed on Rolland Enviro, which contains 100% post-consumer fiber, is ECOLOGO, Processed Chlorine Free, Ancient Forest Friendly and FSC® certified and is manufactured using renewable biogas energy.

Printed in Canada

All Rights Reserved

COPYRIGHT → © 2018 BY SIMON JACOBS

ISBN → 978-1-937512-67-5

Library of Congress Control Number available upon request.

SOME RECOMMENDED LOCATIONS FOR READING PALACES: Alone in a borrowed bed; your friend’s basement; the free verse section in Patti Smith’s cover of “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” repeated ad infinitum; an empty beach after dark; pretty much anywhere because books are portable and the perfect technology!

ANYTHING ELSE? Unfortunately, yes. Do not copy this book—with the exception of quotes used in critical essays and reviews—without the written permission of the publisher.

WE MUST ALSO POINT OUT THAT THIS IS A WORK OF FICTION. Names, characters, places, and incidents are products of the author’s lively imagination. Any resemblance to real events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

For John Baren, wherever you are

Palaces

“And who are these?” said the Queen, pointing to the three gardeners who were lying round the rose-tree; for, you see, as they were lying on their faces, and the pattern on their backs was the same as the rest of the pack, she could not tell whether they were gardeners, or soldiers, or courtiers, or three of her own children.

—Lewis Carroll

CONTENTS

I.RICHMOND, INDIANA

II.MANHATTOSI

III.NORTH

IV.FOYER

AFTERWORD Vandalia, Ohio

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I.

RICHMOND, INDIANA

THE VERGE OF DECEMBER: OUT BACK, AFTER THE show, a late-high school kid native to this town with his ears stretched to the size of clementines, Casey, shrieks and skips back and forth in the middle distance, just slowly and deliberately enough to let each firecracker hit him.

Beyond, skies like you don’t see except in the middle of flat states like Indiana, where the only visible landscape—here, the tops of distant pine trees—is too far back to seem like real life, to be taken seriously, and this kid flickering up from below, a giggling blot on the horizon.

A buddy of yours, I think the frenetic banjo player, offers me a firecracker in the spirit of camaraderie, of inviting a stranger into their midst. “John, right?” he says. I don’t like that he knows my name, that he got it from elsewhere. I hold the firecracker in my hands like a priceless flute.

“Y’all just pull it,” he says. The Southern accent is fake.

Instead, I pass it off to you, unfamiliar at this point but standing incidentally beside me, a presence I haven’t fully processed yet, and shove my hands into my pockets. You take it like a favor and, with a practiced hand, fire away.

It cracks out of your fingers and hits Casey’s bright red leather jacket in a splash of tiny sparks—he yelps and stumbles to the side, the frosted grass crunching beneath his feet. Someone calls out: “Make him dance!”

We watch the display of loud, harmless explosions as your friends let loose, all the ostensible rage and frenzy from an hour before now dispersed into something that seems almost quaint and wholesome, edging on nostalgia. I stand stock-still and feel sweat trickling down my sides, starting and starting.

From that night on, we never stopped running.

II.

MANHATTOSI

A YEAR AND A HALF LATER, IN A CITY TO THE northeast, you catch me easing out the entrance of the museum with my arms wrapped around a human-sized, 17th-century Japanese vase painted in pink and white flowers. It’s early summer and the heat is already trippy and oppressive; we’re awash in sweat and the new thrill of finally having a home base to return to, a domestic excuse for acquiring this artifact.

I’m about to topple from the weight, but suddenly you’re on the stone steps in front of me, skimming your hands over the glossy surface and running through your knowledge of lotus petals and cherry blossoms, the most symbolic of all flowers. I’m staring at the blackening tips of your fingernails, your scalp—the feathery ridge in the center, its tips barely clinging to color, the uneven fuzziness creeping in around it—and thinking about haircuts, about matters of personal hygiene, about showering using a sink.

“This vase is super heady,” you say. You point to a cherry blossom. “Transience”—dragging your finger along a painted whorl toward a lotus—“to resurrection.”

I tell you, distractedly, in the manner of filling conversational space, that the pattern of flowers reminds me of a fourteen-year-old’s idea for a sleeve tattoo, and it takes a second for me to remember that’s basically the design your brother who died in Iraq a year ago had on his arm, and that I’d picked this vase out, specifically, as a sort of memorial to him. I’d stood examining it in the empty gallery, certain that it reminded me of someone close to you, of death experienced at a distance. I remembered, and then promptly forgot.

To divert you from my blunder, I motion with my foot at a passing fashion disaster on the sidewalk, a skulking guy with a massive hiker’s backpack and crooked horizontal stripes shaved across his head, whose remaining hair looks like “the world’s worst corn maze.” It’s enough, and your reaction is bigger than I expect—a full-bodied, guttural laugh and half-collapse, you actually slap your knee, while the vase slips beneath my sweaty fingers—such that it, too, feels like overcompensating to fill polluted space. The man rounds the corner with his spoils, and we negotiate the remaining stairs with ours.

It takes over two hours to get the vase back to our building, and a superhuman effort to haul it from the basement to the third floor, the sounds of our struggle magnified through the stairwell and across the spaces between neighboring buildings, but the whole way no one says anything to us, no one asks about its provenance. That night, when we always pose the most sensitive questions, when we’re wrapped in our individual sleeping bags on the dusty floor like two little cocoons in the big big city, staring up at the crumbling ceiling cast by borrowed light through the empty windows, you ask if I took the vase—out of everything else available and still intact—because it reminded me of something.

It’s the perfect time to mention your brother or, more broadly, willpower itself—the reason we’re lying on this floor, the way we arrived here in the city—to bring up what we’re both denying. Instead, I reach over and brush a swoop of stray hawk from your forehead and say something about our derelict space needing an “aspect of Japan,” but it’s a non-sequitur like my Mia Farrow tattoo is a non-sequitur—thematically distinct from the objects around it. I say pointlessly, reiterating, though I’ve never been there, “It reminds me of Japan.” I say nothing about your hair.

*

Our last year in college, just after we moved together as a couple into the only apartment for which we ever paid rent, back in Richmond, on our first night we sat face-to-face on the second-hand couch and screamed at each other, the taped-up boxes and garbage bags and implements of our moving arrayed arou

nd us: no words, just long, sustained howls, repeated at different pitches and escalating volume until we both went hoarse. Your voice gave first—before our new neighbors started banging on the wall—but not by much. Like many of the gestures we made during that time, it recalled an animal claim about ownership, served as a marker of something (a living situation, a pair-bond) that we thought of as potentially permanent, despite the month-to-month lease and translucent white paint on the walls that hid no history, all of seven months between us and rival human life on every side. When I decided where to position the Japanese vase (which ended up being directly in the center of the living room, or what had once been the living room), you eyed it from the doorway to the stairwell like the presence of any furniture at all was an imposition, then took a running start and slammed into it just to prove the vase wouldn’t topple, that it could take the weight we gave it.

In this new space, our aspiration is to the appearance of abandonment. To the police, the urban adventurer, anyone else who ignored the weathered surveillance placards and bolted door and made their way to the third floor of this building, the vase would register as a solitary, unwieldy piece of decoration left behind by the previous occupants when they moved on, a token bit of randomness, like the single pristine stuffed animal unearthed from a demolished office complex, a sign that some-one had once cared. It wouldn’t betray us.

I’d looked forward to the anonymity of the city, its famous capacity for disappearance. The size really was beyond belief, and in the macro sense, true, I could die virtually without impact, but the promise felt unfulfilled—I hadn’t been able to vanish in the way that I wanted. The first time I rode the subway alone I’d felt noted and itemized, broken into parts; whenever I raised my eyes above my lap I’d seen the man across from me staring beneath his cap, and I sat there caught in a confused mess of acknowledgment, reading menace everywhere, wondering what the problem was, if I exhibited some kind of aberrance I didn’t recognize or had unknowingly breached a fundamental social contract between us, between me and this stranger, these strangers. I felt a tingling sensation pass from one extremity to the next, as if awaiting sudden blood flow, for a visible wound to re-open. I grew all at once more uncomfortable than I had with any cop. I crossed and uncrossed my legs. I watched his shoe—more of a workboot—but couldn’t raise myself any higher. He got off the train at the same stop I did, and I dawdled until he moved off ahead. A part of it was obvious and all too familiar—we’d been fashioning ourselves to look like outcasts since long before we knew each other—but this was supposed to be different.

There was something between us and the city that didn’t take. The facade of urban life was crumbling by the time we arrived, certain institutions had broken open for the taking, and as soon as we stepped off the bus, briefed in nothing, your empty car sitting in a lot X states away, we knew there was no way we were going to live according to someone else’s formula. The vase, an ancient object from a past entirely separate to ours, was as good a marker as a door. We entered and exited at will.

I’m someplace downtown, far from home, when I’m turned out again, sent blinking into the sunlight like someone who’s never seen it. I’m still learning to recognize the places that are patrolled versus those that are now left empty, but this one I entered on purpose, because the building positively bled luxury—stone beasts out front, deco columns into infinity, factory-level air conditioning you could feel from the street whenever the motion-activated doors slid open—and I was curious to see how deep I could go. In fact, I hadn’t even crossed to the bone-colored elevator bay when someone was following me, was communicating via earpiece, was putting his hand on my arm and leading me back to the street.

The stifling summer air hits me full-force, and a feverish dizziness rushes through my body at the sudden temperature shift. Behind me, the guard returns invisibly to his post. Before me, the rest of the day uncoils, filled with unspecified activity. We’ve been in the city for just over a month, the apartment for the last two weeks, and I still have no idea where anything is relative to anything else. I consider retreating to our building and waiting for you, but when I linger there for too long by myself the disrepair and lack of functionality starts to eat at me, as does my inability to address it, and our situation dissolves into an unstable mess of contradictory, half-assed morals, something we wrote too large too quickly, a ’90s squatter myth we were doing wrong. Our departure has felt like a given since before we arrived, since I reached into my backpack on the bus and realized I’d never owned a pocketknife.

A sickening wind blows across the city, and with it the unmistakable smell of baking garbage. The sidewalk is swarming. I watch the people dividing into pairs. A wasted kid in baggy tan clothes activates as a handsomely dressed young woman carrying black paper bags nears him. She pauses when he speaks to her and looks confused, tilting her head minutely, politely forward, like she can’t quite make out what he’s saying. I walk past them. After a minute she cuts him off and takes a few steps away in the other direction; he follows. She speeds up a little, quivering on her thick heels, and he matches her pace, continuing to talk while blocking her off, reaching one hand in front of her like, You haven’t decided where you’re going. I will them to separate, for the crowd to funnel in and redistribute them far apart, but they’re quickly lost in the traffic. I imagine how much our circumstances would have to change for us to switch positions, me with this kid, this woman.

Along the sidewalk, a placid stream of milky-colored water stagnates in the gutter—the summer must be the worst season. I pass a high-end lingerie store advertising scandalous underwear. A bare mattress lies discarded on the side of the street. I consider it theoretically, as a fixture in someone’s home somewhere in the past, sustaining their impact daily, now lobbed out among the populace. I’m amazed by how instantaneously everything can turn to funhouse-like squalor. I could close my eyes, open them, and everything would be different.

A spanging couple is camped under an awning with a sleeping dog and a cardboard sign offering hugs. The dog looks like a prop. I raise my hand to my face as I walk past, really my stretched earlobe, our visual match. I can’t tell if they acknowledge me.

When they’re out of sight, I close my eyes, and take eight steps in the dark. The experience is extremely disorienting, but in a pleasantly weightless way, especially when I don’t immediately collide with anyone. It’s liberating to think that, if I make myself willfully blind, people will make the effort to steer clear. I open my eyes, and voila, it’s you, ten feet ahead, walking with your back to me.

You’re dressed in the type of outfit I haven’t seen since the months just after we met, clothes I didn’t even realize you’d brought to the city: Converse, skinny jeans, a studded belt, and patched leather jacket (ridiculous in the heat), hair combed off to one side, glared by the shaved parts in the sun (mohawk at rest). It strikes me as gratuitous, this ensemble and its impeccable presentation, like a tailored denial of where I thought we stood, of the austerity to which we aspired. A kernel of resentment forms. A cop passes by my left shoulder, spares you a long look. I wonder why you chose today to trot it out—that’s the phrase I use in my head, “trot it out,” like goods on display—and from this distance, the whole of you, your posture looks different: I notice the way you take each step with just an instant of deliberation, a crackling bounce, as if the shoes are brand new and you’re still settling into them, as if this is the first day out in your new disguise. It’s strange to assess under these conditions, like you’re the subject of some basic surveillance, like I’m just one among the many, but, apart and unnoticed, this is what I do. Perversely, I feel like I’m the one being checked up on, like I couldn’t be trusted to take this neighborhood on my own, to reliably pass on the data. I follow you at a distance; I get caught up in it, crouch a little like the caricature of a detective, turn it into a game between me and your obliviousness to my presence.

It’s unclear how long I keep following afte

r I realize the woman ahead isn’t you. Surely, we draw parallel long after I understand that the bearing, the accessories aren’t yours at all. I pick up my pace on the sidewalk, crossing against a light ahead of her, now making directly for the subway but without a specific destination in mind. Just in front of me, a couple approximately our age walks holding hands. As I pass them, I lightly squeeze her free hand and then let it go—a glancing touch, noticeable but unmentioned. It’s a small betrayal, an act of revenge for your absence, for my own misplaced recognition.

Underground, the train is packed enough that I’m still sweating like crazy, despite the air conditioning. I collapse into an empty space on the bench. The people to either side of me shift, and I worry that I’m starting to get that smell, the smell of days spent sweating through the same clothes. At the next stop, the center of the car clears out and I notice that the family sitting across from me—an entire family! mother, father, little boy and girl—are wearing surgical face masks, and all I can think to myself is Finally.

Three stops later—the family gone now, the car emptying—the train stalls at the station. The doors hang open. After a few minutes, I notice there’s commotion in the car behind us. I hear shouting. I look through the window behind me and see people spilling out of the train onto the platform. The conductor comes on over the speakers: “Ladies and gentlemen, we apologize for the delay. A child has been left on the train.”

I stand abruptly and exit the car, an odd ache in my chest. I walk up the platform beside the train, past a ring of onlookers and transit officials with their hands at their hips, clustered around this narrative of abandonment, guilt passing from face to face as the responsibility is shifted from one person to the next, as their humanity is tested. I’m surprised to find myself walking again beside the woman from the street above, who looks like old you. Other than the concerned crowd at one end, the station isn’t busy, and I walk approximately behind her for most of the length of the train, still paused. Inside, at every car, every open door, there’s a man standing: one by one, I watch each of them turn their heads to watch her, as if connected on a series of tripwires or pulled by something beyond their control, each taking a piece. The doors slide closed at last, and a final face rotates in the window, observing from a tank. The train barrels out of the station. Far behind me, the gathered crowd disperses, nothing at its center. I imagine the tunnel filled with water, the eyes drowned and blank. We walk up the stairs, the tiled walls punctuated with posters of missing people.

Palaces

Palaces